The Owen-Spalding Climb

This is the quickest, safest and easiest climb on

the Grand Teton when the route is dry and the weather is perfect. Under those conditions it's a suitable objective for many athletes who wish to climb this mountain without a rope in a single day. Previous climbing experience is not a prerequisite but it isn't for everybody. It demands agility, finesse and vigilance.

The Jenny Lake Climbing Rangers believe that "climbers should not attempt a one-day ascent of the Grand Teton without prior experience on this LARGE mountain and familiarity with technical ascents in the Teton Range" and they warn that "soloists have been injured or killed attempting these routes."

The second party to summit the Grand Teton (2nd verified party) had no knowledge of the area, no similar climbing experience and no gear. They free-soloed the Owen-Spalding route in a single day back when there was no climbers' trail, no guidebook and no internet. Quin Blackburn, Dave DeLap, and Andy DePirro did that in 1923. It stands to reason that more than a few people can follow in their footsteps with the resources available today. Indeed, many do. As Renny Jackson says in his Guide to the Teton Range, soloing in a day is "commonplace during the summer when the route is dry." And as to the first one-day ascent, he says it "was in the finest of traditions: a small, light expedition that shunned all notoriety."

While you don't need to be an "accomplished athlete" to climb the Grand Teton, it helps. Safely soloing this mountain in a single day requires aerobic fitness, muscle endurance, agility, coordination, strength, flexibility and balance. A climber on a multi-day guided trip doesn't require the same level of fitness but it's far easier and more enjoyable if you're fit. Having said that, this mountain has been climbed by blind people, 6-year-olds, 81-year-olds, people missing an arm or leg, an adult with Down syndrome, and out-of-shape flatlanders with no climbing experience whatsoever. Most are guided by friends or the park's climbing concessionaires. And most of the referenced people should never free solo or try a round-trip in a single day. It also helps to be acclimated to the elevation.

Free-soloing this route under mixed conditions is not recommended. The difficulty & danger increases as does the time needed to get up and down the mountain. Of course, a little bit of snow, ice or wet rock is pretty common. Some climbers can manage those conditions with ease. Professional guides have misjudged the hazards & died on this route so don't make the decision to solo under mixed conditions lightly. The Rangers occasionally post updates on conditions to Instagram. Our homepage sometimes has updates and news. You can keep track of the forecast for the Lower Saddle & the summit's forecast to get a feel for any changes to the conditions.

It's impossible for us to know how easy the climb will be for you, how well you will manage the hazards or how elastic your comfort zone will be. And nothing we say can convey the experience quite like being there in person. If you're looking for bubble-wrapped adventures, visit Six Flags Magic Mountain.

Free-soloing this route under mixed conditions is not recommended. The difficulty & danger increases as does the time needed to get up and down the mountain. Of course, a little bit of snow, ice or wet rock is pretty common. Some climbers can manage those conditions with ease. Professional guides have misjudged the hazards & died on this route so don't make the decision to solo under mixed conditions lightly. The Rangers occasionally post updates on conditions to Instagram. Our homepage sometimes has updates and news. You can keep track of the forecast for the Lower Saddle & the summit's forecast to get a feel for any changes to the conditions.

It's impossible for us to know how easy the climb will be for you, how well you will manage the hazards or how elastic your comfort zone will be. And nothing we say can convey the experience quite like being there in person. If you're looking for bubble-wrapped adventures, visit Six Flags Magic Mountain.

There's less than 300 feet of climbing that might test

your natural abilities. Some of that climbing goes by a

large drop-off. It causes more than a few people to reconsider their plans. The Owen-Spalding is a Class 5.4 climb on the YDS scale of difficulty when dry, "suitable for beginners."

For the record, people often shorten the name of the Owen-Spalding route to the "OS", saying the "O" "S" when speaking. It's also common to hear "The Owen".

The Approach

Visit our webpage for The Hike to the Grand Teton's Lower Saddle if you need more details about the approach than what follows. It has tips and info not covered here. Just south of Jenny Lake in GTNP is the Lupine Meadows Rd which takes you to to the Lupine Meadows Trailhead. Almost everyone starts their trip from there. It's 21 miles from the Town of Jackson.

Water

is found at many places along the trail. About 5 miles in, the

climbers' trail crosses the

source of spring water feeding Spalding Falls. We always make sure to

have enough water to get there. The water below

the

falls may need filtering because too many people use the landscape as a toilet.

The South Jenny Lake Store has a free outdoor water filling station if you need some clean tap water before leaving the trailhead.

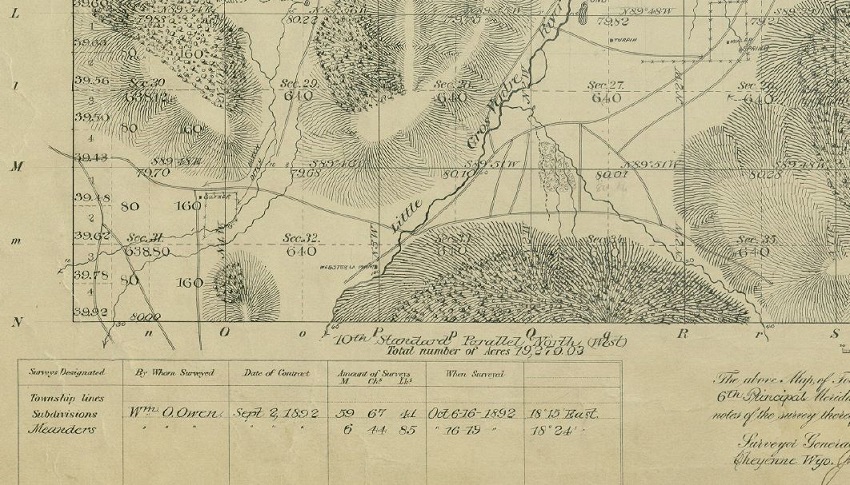

The elevations shown on the image are based on an out-of-date datum. The official NGS elevation of the Grand Teton is 13,775 ft. It's also outdated. It's common to see 13,781' on many online maps but the Feds haven't officially released a new elevation. Local surveyor and climber Rich Greenwood

got an opportunity to take a Trimble 4000ST GPS receiver up the mountain in October of '91. You can read about their adventures and the original Grand Teton surveys in a PDF file of the article published by Point of Beginning Magazine in 1992. Newer Topographic Lidar Surveys have taken place over GTNP and are available online.

Assuming you're walking fast & traveling light, these are common split times and distances from the Lupine Meadows trailhead to the Lower Saddle:

First Junction: 30 minutes, 0.5 hrs total, 1.7 miles

Second Junction: 30 minutes, 1 hr total, 3 miles

Platforms Camping Zone: 4.1 miles

Platforms Camping Zone: 4.1 miles

Meadows Camping Zone: 30 minutes, 1.5 hrs total, 4.5 miles

Caves Camping Zone: 5.2 miles to spring water

Moraines Camping Zone: 5.9 miles to sign

Lower Saddle: 60 minutes, 2.5 hrs total, 6.4 miles

Caves Camping Zone: 5.2 miles to spring water

Moraines Camping Zone: 5.9 miles to sign

Lower Saddle: 60 minutes, 2.5 hrs total, 6.4 miles

Summit: time varies with skill, fitness and route knowledge

(The distances are estimated from GPS tracks)

(The distances are estimated from GPS tracks)

It's

2,175 vertical feet to the summit from the Lower Saddle. The slope

distance is longer and some climbers do more zigzagging than others.

A handful of runners reach the Grand's summit in under 2 hours from the

trailhead. Local athletes regularly reach the summit in under 3.5 hours just by walking at a very fast clip. Many parties take 24 hours to make a single-day round-trip. None knows how long it will take you.

Conditions, acclimation, skill set, fitness, injuries, age, route knowledge, weather, hydration, fuel, sleep, mental state and gear all play a part in how fast you'll move. The rangers warn that some climbers using protection have taken 10 hours to reach the summit from the 11,600' Lower Saddle.

The distances shown above are close to the map distances shown on p.266 of Renny's 2023 guidebook. However, on p.525 of Renny's guidebook, he says "the Lower Saddle is about 7.5 miles from the valley floor." Clearly a mismatch nobody corrected. It's not the only one. Exum Mountain Guides said it's "over 7,000-feet and approximately 8 miles" to the summit on their website in 2025, with a "strenuous seven-mile, 5,000-foot hike to the Lower Saddle" from the trailhead. And we recorded a 16.18 mile round-trip on an old NPS-issued Garmin handheld GPS back in 2017. In the 2nd edition of Select Peaks of Greater Yellowstone, Tom had a distance of 10 miles to the summit along the OS route. That was Tom's best guesstimate when he wrote the 1st edition, and it remained unchanged in 2023's 2nd edition. BTW, Garmin's first GPS watch came out the same year as Tom's 1st edition of Select Peaks, in 2003. The iPhone came out in 2007. The output of a GPS watch's calculations can vary due to many factors including the user's speed, route choices, barometer vs GPS elevation, etc.

The distances shown above are close to the map distances shown on p.266 of Renny's 2023 guidebook. However, on p.525 of Renny's guidebook, he says "the Lower Saddle is about 7.5 miles from the valley floor." Clearly a mismatch nobody corrected. It's not the only one. Exum Mountain Guides said it's "over 7,000-feet and approximately 8 miles" to the summit on their website in 2025, with a "strenuous seven-mile, 5,000-foot hike to the Lower Saddle" from the trailhead. And we recorded a 16.18 mile round-trip on an old NPS-issued Garmin handheld GPS back in 2017. In the 2nd edition of Select Peaks of Greater Yellowstone, Tom had a distance of 10 miles to the summit along the OS route. That was Tom's best guesstimate when he wrote the 1st edition, and it remained unchanged in 2023's 2nd edition. BTW, Garmin's first GPS watch came out the same year as Tom's 1st edition of Select Peaks, in 2003. The iPhone came out in 2007. The output of a GPS watch's calculations can vary due to many factors including the user's speed, route choices, barometer vs GPS elevation, etc.

GAIA's approach to the Lower Saddle

Strava tracks to lower saddle

More Garnet Canyon Data from GAIA GPS

Strava tracks to lower saddle

More Garnet Canyon Data from GAIA GPS

Traveling under darkness is a bigger challenge if you don't know the area. It's not a foolproof approach. People do get off trail during daylight hours but it's less common. Be wary of letting partners run ahead or lag behind. Every year this doesn't work out well for one or more of the party members.

The dry summer trail to the Lower Saddle disappears for over 200 feet at two boulder fields (see above map). The trail resumes to your southwest on the ascent. Much of Garnet Canyon is a giant boulder & talus field but some areas are more bouldery than others.

The trail disappears in an insignificant way for a short distance in several locations. Usually, the trail continues just in front of you. Take the path of least resistance.

Click to Enlarge

Climbers use a bootpack to gain the top of the Lower Saddle as we enter the summer season, and sometimes well into the summer season. The bootpack can change from icy to perfect to a sloppy mess in a single day. An ice axe may be necessary. Maybe crampons. Some also use hiking poles.

There's a rope that's affixed to the saddle's headwall. It's used once the snow burns off the saddle's trails. The "opening date" varies each year but it's usually in July, often by mid-July. In 2011, it was the 2nd week of August (big snow year). In 2025, the fixed rope was being used during the 4th week of June.

The guides use their own rope to belay clients at the headwall.

~~~~~~~~~~

Never remove any hiking poles or ropes from this area. They are not abandoned, just set aside.

Climbers typically ascend the Meadows Headwall closer to the Middle Teton's NE aspect when winter snow covers

the canyon's floor. They usually avoid the summer trail by Spalding Falls because it's considered to have an elevated threat level. Either way, all areas have elevated threats with snow underfoot.

Snow and ice are the most common variables in backcountry rescues and deaths in Grand Teton National Park. Know how to travel over snow. Do not underestimate the threats be it on the approach or a climb. Avalanche hazards must be mitigated during the winter and spring. Avalanches have occurred at other times such as early November but they're less common. Wait for the trails to dry up if you wish to limit your exposure to summer snow.

Meadows Headwall - SpringtimeSnow and ice are the most common variables in backcountry rescues and deaths in Grand Teton National Park. Know how to travel over snow. Do not underestimate the threats be it on the approach or a climb. Avalanche hazards must be mitigated during the winter and spring. Avalanches have occurred at other times such as early November but they're less common. Wait for the trails to dry up if you wish to limit your exposure to summer snow.

Parts of the Grand Teton's Lower Saddle can be seen from a few areas as you approach the Meadows Camping Zone but the Lower Saddle mostly hides behind the Meadows Headwall.

Trail above the Meadows Camping ZoneShortcutting the switchbacks just above the Meadows (to the right of Spalding Falls) contributes to erosion, rockfall, and damages

sensitive vegetation. Stay on well-traveled paths whenever possible for everyone's safety and to protect park resources.

You may see a few side trails just above and just below the top of Spalding Falls. Some go to climbing areas like Irene's Arete. Others are used to avoid early-season snow. Some are shortcuts.

Climbers use a bootpack to gain the top of the Lower Saddle as we enter the summer season, and sometimes well into the summer season. The bootpack can change from icy to perfect to a sloppy mess in a single day. An ice axe may be necessary. Maybe crampons. Some also use hiking poles.

There's a rope that's affixed to the saddle's headwall. It's used once the snow burns off the saddle's trails. The "opening date" varies each year but it's usually in July, often by mid-July. In 2011, it was the 2nd week of August (big snow year). In 2025, the fixed rope was being used during the 4th week of June.

The guides use their own rope to belay clients at the headwall.

Lower Saddle's Fixed Rope

This is a rockfall zone. Stay alert.

~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~

Never

travel directly above the Fixed Rope to the west or northwest during

the summer. There's a high probability of causing rockfall on climbers

below you. In some locations the rock is too unstable to remain in place no matter how carefully you move. Head southwest toward the Middle Teton. If it's off-season and none is around, do whatever you want but stay off the vegetation.

~~~~~~~~~~

The

fixed rope drapes over a drainage. Climbing the headwall without using

the rope is common when the drainage is dry but most will use the rope

to some degree. If you struggle with the climbing at the fixed rope then free-soloing is not for you. You can contact the Jenny Lake Climbing Rangers to find out if the approach is free of snow or if the fixed rope is being used. Or check their Instagram page.

Never remove any hiking poles or ropes from this area. They are not abandoned, just set aside.

Upon leaving the fixed rope, climbers head for the southeast corner of the saddle and they end up by a camping site and a source of water.

Lower Saddle Rules

The water source is at the toe of the Middle Teton's rocky slope. Just to the north of the hose is a large seepage area. Look for the well worn landscape near the southern edge of the vegetation. You'll find a section of garden hose in a shallow drainage. In the above photo, the hose is by the climber in the red shirt.

People have been drinking this water unfiltered (and untreated) for decades. We never filtered it; however, there's no guarantee it's always safe to drink. And the hose may become contaminated by unwashed hands. Sometimes it needs filtering for particulates but it's usually fine. BTW: Symptoms of giardiasis normally begin 1 to 2 weeks after becoming infected. It won't happen quickly.

It's possible for the saddle's water source to dry up, usually in September. It can spring back to life with the changing weather. You can get water from the Middle Teton Glacier if water disappears at the saddle. Make sure you have enough water for the trip to the summit. Rainstorms and lingering snow can put water in the drainages between the Grand's lower & upper saddle but don't count on that.

Two huts are assembled at the saddle every season. A third hut—used by the JH Mountain Guides—sits above the trail to the Morainal Camping Zone. Look toward the east face of the Grand Teton by Teepe Pillar to see that hut.

There's a gear hanger just north of the huts should you wish to drop some weight. A bear box is available to store food from critters like marmots and pikas. They will happily destroy your tent to get food. In addition to them, you might see chipmunks, ravens or an invasion of butterflies. It's rare to see bears, foxes, bighorn sheep and mountain goats at the saddle but they have made visits (mountain goats are considered non-native and the park has culled them).

The rest stop on the western aspect of the saddle is for privacy. It's not a functioning toilet. It's west of the Exum hut. You're required to pack out human waste using WAG bags, etc. If you ran out of WAG bags, the rangers might have an extra bag in their hut. The rangers aren't always at the saddle. Do not pee anywhere near camping spots. Use the toilet, or somewhere else on the western aspect of the saddle.

There are small rock shelters on the western aspect of the saddle including one next to the rest stop. Most are north of it. Those shallow caves are attractive places to seek shelter during a storm but they might increase your chances of getting hit by lightning. We don't remember anyone being injured by lightning at the saddle but plenty of people have been zapped on the Grand.

Most people get cellular service at the saddle & above it. It's a good place to check the forecast. Saddle temperatures

can stay in the 50's on the warmest summer nights. On the coldest summer

nights, temperatures dip below freezing and it can snow at the saddle. In July of 1993, 6 feet of snow fell

at the Lower Saddle and it was the coldest & wettest summer on

record. The saddle also has a well-earned reputation for strong winds. 117.5 mph gusts were recorded on June 16, 2016.

The Owen-Spalding Climb

From the Lower Saddle, you're heading north along the saddle's crest toward the Black Dike. There's a trail. It's mostly scrambling, uphill hiking and a few climbing moves to reach the more technical parts of the Owen-Spalding which start at the Grand Teton's Upper Saddle.

You're headed for the western side of the Central Rib's Needle once you pass the dike. Don't head toward the Needle's eastern side. Also, the Idaho Express and the Wall Street Couloir are not good routes to reach the Upper Saddle.

Many climbers leave hiking poles by the dike. Once again, leave all gear where you find it. The dike is

made of black diabase which formed from molten material. It's the same type of dike as seen on the Middle Teton and Mt Moran.

You're headed for the western side of the Central Rib's Needle once you pass the dike. Don't head toward the Needle's eastern side. Also, the Idaho Express and the Wall Street Couloir are not good routes to reach the Upper Saddle.

The area between the Lower (11,600ft) & Upper Saddles (13,200)

The main drainage sees weekly rockfall events caused by other climbers. Bowling alley is the favored description. Most climbers stay out of the drainages whenever possible. Crossing them is common.

Just a quick safety note to non-climbers:

If you're unfamiliar with climbing etiquette, the appropriate thing to do if you kick rocks down the mountain, or see rocks falling down the mountain, is to holler 'ROCK'! even if you see none below you. It's like saying FORE! when you make an errant golf shot. Your safety and the safety of others is everyone's responsibility when it comes to falling rock.

Don't let down your guard on the scrambles. On August 9th, 2005, a 47-year-old local woman climbing with Exum Mtn Guides tumbled about 15

to 20 feet while descending by the Needle and sustained injuries to her

knee and ankle.

Bootpacks up drainages are useful when encountering stable snow; however, the drainages are one of the most common locations for serious snow-travel accidents due to the steepness, small cliff bands and rock outcroppings.

On July 30, 1995, Clay Roscoe (26) and Megan T. Piper (25) were descending from the Upper Saddle when they decided to use the “Idaho Express” couloir instead of the standard routes by the Owen-Spalding Couloir. Piper slipped on snow, went over cliff bands and died from trauma to the head and neck.

On June 23, Slovenian national Amer Beslagic (38) was nearing Upper Saddle when he presumably fell on icy snow and slid between 1,000 and 1,500 feet down the Idaho Express. He was wearing crampons and carrying an ice axe. The cause of death was severe head injury and total body trauma.

Back to our climb...

As you move past the western aspect of the Central Rib's Needle, you'll come across the Chockstone Chimney on your right. It's the first opening along the Needle's western aspect. It allows us to access the Central Rib's Bench. The bench usually provides a safer line of travel to the Upper Saddle.

Many variations to gain the Central Rib's Bench

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

The two most common variations to access the

Central Rib's Bench are:

1) the Eye of the Needle via the Chockstone Chimney

2) the Briggs' Slab

The Briggs' Slab is a common

guided variation. They also use others. The slab is easy to get to when dry and it's easy for guides to

quickly belay clients across the slab. You can reach the slab from the chimney but most climbers take an easier, safer and longer approach to reach the Briggs' Slab. The Middle Ledge variation is a good alternative to both the slab and the lower chimney.

If you're an experienced mountaineer, you can reach the Upper Saddle

without getting into the fine details shared below.

This is the Central Rib's "bench" we're trying to accessLet's look at the two most common options in greater detail, starting with the chimney...

The

guided climbers in the above image are descending from the Briggs' Slab and

about to pass the Chockstone Chimney. They're staying on a slightly elevated path above the actual

drainage. Staying just above the drainage sometimes provides an extra measure of safety. The clients are less likely to kick loose rocks down the slope, or slip on them, or be hit by them. And the drainage can be wet and icy.

Anyone can follow the guides. It's everyone's mountain. They're not in charge of other climbers. People head off in questionable directions all the time so don't just follow any climber.

Anyone can follow the guides. It's everyone's mountain. They're not in charge of other climbers. People head off in questionable directions all the time so don't just follow any climber.

Take the Chockstone Chimney or go for the Briggs' Slab

Scrambling up the ledge/step/slab system just to the left of the chimney is common. Most reenter the chimney just above the lowest chockstones. That's often safer and faster. Choose any line that looks good for you. The

chances of rockfall from those above you is something to consider in the chimney. We avoid going straight up the chimney with weaker climbers or young kids. If these options look unappealing, just head for the Briggs' Slab. Or use the Middle Ledge variation which runs just below the Briggs' Slab.

Let's look in the chimney...

A few variations near the bottom half

Many people who take the "Narrow Ledge" variation end up climbing an easy southeast corner inside the chimney. Others climb to the Runner's Slab along the chimney's northern side.

Mid-chimney

On August 31, 2003, two climbers got stuck on the mountain for three days during a snowstorm. On their third day, climber Joe Hestick broke his hip and several ribs after taking a fall while descending the Chockstone Chimney.

The Eye of the Needle is a natural tunnel. It's a tight fit if you have a big backpack. And watch your head. The Eye's tunnel may be plugged with snow early in the season. Once out of the tunnel, climbers traverse under or over the Belly-Roll Almost. Both variations work fine. If you go under the Belly-Roll Almost, you'll be looking for a small foothold that's out of view until you're directly above that foothold. There are excellent handholds.

On Aug 10, 1994, Chris Schneider fell down the Chockstone Chimney from the Eye of the Needle area and sustained serious injuries to his head and back.

On Aug 10, 1994, Chris Schneider fell down the Chockstone Chimney from the Eye of the Needle area and sustained serious injuries to his head and back.

On Sept 5th, 2025, a 57-year-old male climber had to be short-hauled from the Eye of the Needle area (possibly at the Belly Roll Almost); and then, the very next day, a 31-year-old female was short-hauled after experiencing a head injury from rockfall by the Briggs' Slab area.

While Emelie Forsberg was attempting a woman's fastest known time (FKT) on the Grand Teton, she used the Eye of the Needle variation during her descent and took the Runners' Slab near the bottom of the Chockstone Chimney. It wasn't the shortest way off the bench but she did it pretty quickly running with Kilian Jornet the day before he ran his FKT on the Grand.

Kilian also took a 3:23 round-trip training run up the Grand with Anton Krupicka. About a month later, Anton took the FKT for Wyoming's highest peak, Gannett, on September 18, 2012: 8h46m32s car-to-car from Green River Lakes. His time was beaten (barely) in 2020, by Aaron Robson of Lander, WY, with a time of 8h 39m 26s.

Kilian also took a 3:23 round-trip training run up the Grand with Anton Krupicka. About a month later, Anton took the FKT for Wyoming's highest peak, Gannett, on September 18, 2012: 8h46m32s car-to-car from Green River Lakes. His time was beaten (barely) in 2020, by Aaron Robson of Lander, WY, with a time of 8h 39m 26s.

Emelie & Kilian on her FKT in 2012 (Chockstone Chimney)

Everyone scrambles at a different pace over different types of terrain so it's hard to say what line is fastest for any one person. Many variations are available including early-season snow lines. BTW: In 2013, a NY Times reporter said Kilian rolled "one of his thick ankles to a tendon-straining angle, then began to hop up and down on it nonchalantly" while he watched in horror. That oddball ability to withstand a rolled-ankle injury is one reason he's fast on his feet over questionable terrain.

(Click to Enlarge)

Another look

There are some shortcuts by the rockfall zone but they're usually avoided.

The Briggs' Slab is named after Bill Briggs. Guides use a friction

belay over rock to quickly move clients over it. It's a good choice for kids when roped.

The Briggs' Slab

Let's look at the area above the slab...

The three climbers in the background are nearing the Belly-Roll Almost after leaving the Eye of the Needle. The guided climbers are descending and getting ready to be belayed over the Briggs' Slab (unseen to your right - west).

The drainage between the two groups is just an extension of the Chockstone Chimney. Climbers heading for the Upper Exum Ridge will follow the extension and cross over the ridgeline. Do not follow them.

You're heading north for the Upper Saddle.

The drainage between the two groups is just an extension of the Chockstone Chimney. Climbers heading for the Upper Exum Ridge will follow the extension and cross over the ridgeline. Do not follow them.

You're heading north for the Upper Saddle.

Conditions on the Briggs' slab may force you to choose another variation. Or the slab may be busy with guided climbers. The Cracks of Doom variation is pretty easy but harder than the slab. There are several lines on the face which vary slightly in difficulty.

The Mini Black Dike runs directly to the Sack of Potatoes chimney. The "High Line" shown above is pretty easy and it's good for an ascent or descent. The High Line can be accessed from the SOP's chimney if you exit to the north instead of taking the direct line up the chimney. Stepping over the chimney along the High Line requires extra care. It's a little awkward and the loose dirt and rocks make it sketchier. The "Southern Line" is your third option. The shaded SOP area is usually icy after a cold & wet weather system. Sunseri considered the SOP area as the fastest line for him on his FKT run.

Connor dropping from the High Line into the Sack of Potatoes chimneyThe Mini Black Dike runs directly to the Sack of Potatoes chimney. The "High Line" shown above is pretty easy and it's good for an ascent or descent. The High Line can be accessed from the SOP's chimney if you exit to the north instead of taking the direct line up the chimney. Stepping over the chimney along the High Line requires extra care. It's a little awkward and the loose dirt and rocks make it sketchier. The "Southern Line" is your third option. The shaded SOP area is usually icy after a cold & wet weather system. Sunseri considered the SOP area as the fastest line for him on his FKT run.

Ascent out of the SOP chimney area - Exit to the High Line variation

The Sack of Potatoes variations are not climbed on a daily basis

like the Briggs' Slab but they do get used.

Now that we're on the Central Rib's Bench, let's head for the Upper Saddle.

The CR's Bench area

It's wise to choose a path that provides

some protection from rockfall. That path can change when other climbers

are above you. There's a small chute-like travel line that guides often follow to reach the Upper Western Rib or the Black Rock Chimney variations. It's not necessarily the fastest line but

it's often a safer line. It sits higher than the travel lines through the bench's low spots.

Looking back down the Central Rib

Another look

You may see scrappy footpaths between here and the Upper Saddle. Some are useful, some not so much.

Central Rib Overview

Click to enlarge

Another Look

There are three common variations to reach the Upper Saddle once you're on the Central Rib's Bench. They are the Upper Western Rib, the Black Rock Chimney and the Rosenberg Variation by the Black Rock Chimney. Let's take a look at the Upper Western Rib variation first.

The Upper Western Rib Variation

Climbers

leave the Central Rib's Bench and cross the slope above the couloir's drainage

chimney to reach the Upper Western Rib. The drainage chimney is not considered to be a safe approach or descent

path due to rockfall hazards. And it's often wet or icy.

The Upper Western Rib is a natural line to follow so most climbers choose it.

A snowy Owen-Spalding Couloir

Climbers have taken slides to their death due to the tricky snow conditions.

In June of 1992, H. Kammeyer (33) lost control in soft wet snow near the top of the

Owen-Spalding Couloir. He went over some rock bands and ended up on the

snow about 100 feet above the Black Dike with bilateral wrist fractures,

a right side pneumothorax, and fractures of T-8, T-12 and C4-7 vertebrae. A helmet probably saved his life.

In 1977, Jackson Hole Mountain Guide Thomas Raymer was guiding Robert Slater

down the mountain from the Upper Saddle in fresh snow when Slater's

pack caught on a rock and they both fell 200 feet. Slater suffered minor

injuries but Raymer was seriously injured and was carried out the

following day. Raymer had a broken femur & talus, and severe scalp lacerations with part of the skull exposed.

Overview of the upper Central Rib - looking SE.

If you're on the Upper Western Rib, you'll want to cross the drainage once the couloir opens up and it's easy to regain the Central Rib. The marked paths are a general direction of travel in the above image.

At the top of the Central Rib is the Patio (seen above). It's a

natural flat area where guides often take a

break. The wind tends to blow and the

temps seem to drop at the Upper Saddle

so the Patio's a good place to add an extra layer and grab something to drink or eat before the technical climbing begins.

The Black Rock Chimney

& Rosenberg Variation

& Rosenberg Variation

Let's go back down the Central Rib and take a look at the Black Rock Chimney area. We'll look at the Rosenberg variation first.

BRC & Rosenberg Variation

You can't miss the black-colored rock on the Rosenberg variation when everything's dry. It

sticks out from the Central Rib like a sore thumb. It tops out at the same location as the Black Rock Chimney.

You can gain the

Rosenberg from many locations so choose any that suits you. You're

heading toward the Central Rib's ridgeline and exiting just south of a

tower-ish rock outcropping on the ridgeline (see picture above).

On September 3rd, 1964, Mrs. Rosenberg was descending this line while on a guided trip. She fell into the main couloir and tumbled for several hundred feet down a snowfield where she was found dead.

Let's look at the Black Rock Chimney variation:

The Black Rock Chimney was considered for removal as a guided option by Exum Mountain Guides in 2022, due to increasing hazards from loose rocks. Back in 2024, it looked like someone sent in the housekeeping team and cleaned up some of the hazards. But, hazards remain and you'll want to exercise caution because the erosion also continues.

On June 17, 2013, Grand Teton National Park rangers rescued 57-year-old climbing guide Jim Williams after the snow that he was standing on near the Black Rock Chimney collapsed and he took a short fall, catching a crampon on the ice and sustaining an injury.

On June 17, 2013, Grand Teton National Park rangers rescued 57-year-old climbing guide Jim Williams after the snow that he was standing on near the Black Rock Chimney collapsed and he took a short fall, catching a crampon on the ice and sustaining an injury.

Access to the BRC

The last 50 feet or so of the approach to that large slab of reddish-orange rock from the south has plenty of loose rocks which are a hazard. We often travel up the bench a little further west of the ridgeline and then head east to reach the BRC & Rosenberg variation.

The short chimney by the slab leads to a steppy ramp that rises above the slab. The ramp ends at the bottom of the Black Rock Chimney. The chimney runs just under the ridgeline's western crest. The BRC meanders more than the Rosenberg variation so it may give kids a short mental and physical break compared to the more direct Rosenberg line.

Jeff at the bottom of the Black Rock Chimney

The

yellow and green arrows in the above picture are two travel options

right above the ramp. For young kids, the yellow line might be easier to

manage with an adult by a child. Just depends.

If you're heading for the Steppy Ramp on the descent, go all the way down the BRC until the ridgeline opens up and you're suddenly on the eastern aspect of the ridgeline. The Steppy Ramp is right at that demarcation or transition point. From there, you're forced to take the eastern aspect of the ridge or the ramp to the west. Take the ramp to the west.

If you did miss the exit to the Steppy Ramp during the descent, you would end up on the eastern aspect of the rib where you'd find some slow-moving climbing over some slabs and ledges compared to the ramp. You can regain the Central Rib's Bench further down the rib's eastern aspect by using the crossovers that Upper Exum Climbers use. You can certainly go that way. We sometimes use that line if it's dry when we're doing a lap on the Upper Exum Ridge.

The young child in the green helmet looked to be 6-years-old or younger and rather unhappy with the whole adventure, or too exhausted. And moving at a snail's pace - truly snail's pace. While very young kids have summited the Grand, most find feeding chipmunks more interesting, fun, and rewarding. Think twice before bringing very young children on this mountain. Same with some adults.

Black Rock Chimney

The western side of the chimney may prove safer for passing loose rocks in the drainage line.

The bowl-like opening above the BRC and Rosenberg variations- looking SSE

Do not take the bowl's drainage to the Wall Street Couloir. It's not a time-saving shortcut — it's a little funky and has no advantages for free-soloing climbers. You can sometimes see climbers on the Upper Exum's Wall Street shelf or along the ridgeline from this location. After exiting the "bowl" on the ascent, you'll stay pretty close to the

western aspect of the Central Rib until you come to the Patio.

Before we leave the "bowl", let's take a closer look at the exit from the top of the Black Rock Chimney & Rosenberg variation.....

Before we leave the "bowl", let's take a closer look at the exit from the top of the Black Rock Chimney & Rosenberg variation.....

Top of BRC & Rosenberg

In the photo, the top of the Rosenberg is immediately to your right on a descent as you exit the bowl. The Black Rock Chimney parallels the Central Rib's ridgeline along its western aspect.

The view from the top of the Central Rib

There's a small, circular rock formation on the Enclosure's summit that was most likely left by Native Americans. At times, non-natives have rearranged it. It's a nice place to

watch climbers on the western aspect of the Grand Teton. The Enclosure

is the consolation prize that guides dish out when the

Owen-Spalding route is a questionable

proposition. They'll talk it up as if it's a treasure of biblical

significance to help everyone feel better about not tagging

the Grand's summit. It's an oddball scramble and it rises higher than any peak in the Teton Range other than

the Grand. The scramble to the Upper Saddle from the Patio area has some foot traps that are easily hidden by unconsolidated snow. Take the time to check your footing. Of course, any kind of snow can cause trouble.

Late on the afternoon of June 11, 1994, Mike Tucker and Bill McDonald of Pocatello, ID, were a short distance below the Upper Saddle when McDonald slipped on moderately steep snow and began sliding. McDonald slid approximately 300 feet before going over a 150 foot cliff-band, then continued sliding another 500 feet down a couloir. He sustained massive head trauma in the fatal fall.

In August 17, 1993, Corbin Rich (17) from Idaho Falls was a short distance below the Upper Saddle when he slipped on snow, failed to self-arrest, and fell about 1,000 feet down a steep couloir containing mixed rock and snow. He died of massive head injuries.

On August 1, 1995, a 25-year-old woman from Portland, Oregon, lost her footing below the Upper saddle, slid about 60 feet, went over a low angle rocky area, and fell another 40 feet into a moat. She died from head and neck trauma suffered in the fall. See "Thursday, August 10, 1995" report in link.

On October 10, 1978, Carlos Medrano was crossing a hard steep snow patch on his way to the Upper Saddle when he slipped and fell over 800 feet over snow, rock and several short cliffbands. He died.

Late on the afternoon of June 11, 1994, Mike Tucker and Bill McDonald of Pocatello, ID, were a short distance below the Upper Saddle when McDonald slipped on moderately steep snow and began sliding. McDonald slid approximately 300 feet before going over a 150 foot cliff-band, then continued sliding another 500 feet down a couloir. He sustained massive head trauma in the fatal fall.

In August 17, 1993, Corbin Rich (17) from Idaho Falls was a short distance below the Upper Saddle when he slipped on snow, failed to self-arrest, and fell about 1,000 feet down a steep couloir containing mixed rock and snow. He died of massive head injuries.

On August 1, 1995, a 25-year-old woman from Portland, Oregon, lost her footing below the Upper saddle, slid about 60 feet, went over a low angle rocky area, and fell another 40 feet into a moat. She died from head and neck trauma suffered in the fall. See "Thursday, August 10, 1995" report in link.

On October 10, 1978, Carlos Medrano was crossing a hard steep snow patch on his way to the Upper Saddle when he slipped and fell over 800 feet over snow, rock and several short cliffbands. He died.

At

this point, you're above the Middle Teton. Enjoy the views. The Grand

Teton rises about 1000 ft higher than the 12,809' elevation of the

Middle Teton. The Upper Saddle is near 13,200 ft.

Upper Saddle - looking W & SW

Variations to access the eastern side of the Upper Saddle

Another look at the southern line

The middle line is very useful when conditions make the other options too sketchy (unstable snow, icing, etc), or everything's backed up. It has small holds but it works fine. It might make a novice climber uncomfortable without protection or spotting.

The southern line

The ascent over the chockstone challenges many climbers on the southern line. The guides will sometimes place a stepping stone below the chockstone to

help climbers get over it. Young kids may need a leg up.

In July of 2014, Mary “Mimi” Conley Bilyeu was above the chockstone when she fell into the gully directly below here. She did not survive. She may have slipped on loose rocks, lost her balance or tripped over her own feet. No one really knows. She was not roped up. She was an experienced climber and being guided at the time.

In July of 2014, Mary “Mimi” Conley Bilyeu was above the chockstone when she fell into the gully directly below here. She did not survive. She may have slipped on loose rocks, lost her balance or tripped over her own feet. No one really knows. She was not roped up. She was an experienced climber and being guided at the time.

A rare variation runs along the seam on the south-facing wall just before the common southern line. It's seen above and below....

The northern route might be the easiest and fastest ascent line for most climbers. The biggest issue with this line is its exposure to the north and the awkwardness of a descent for novice climbers.

On August 4, 1977, Doug Calloway (17)

was climbing the Owen Spalding Route on the Grand Teton a short

distance above the Upper Saddle. A rock was dislodged by his partner’s

rope striking him on the back of the head causing a small laceration,

and a large bump upon the back of his head.

On July 21, 2015, Tucker Zibilich, 26, was desending from the Upper Saddle when a large boulder dislodged and rolled over his arm, causing severe injury to his limb and prompting a rescue by rangers.

On July 21, 2015, Tucker Zibilich, 26, was desending from the Upper Saddle when a large boulder dislodged and rolled over his arm, causing severe injury to his limb and prompting a rescue by rangers.

SAFETY REMINDER

Some people get summit fever when they should be bailing. Or making a temporary retreat (depending on the circumstances). If the weather, conditions or skill sets aren't in your favor, it's time to turn around. It's never the wrong call to bail even if you're wrong about the threat. This is especially true if you're responsible for the safety of others. A few groups who couldn't outrace the weather experienced life-changing injuries and death.

Test your holds to make sure they'll support your full weight. Look for slip hazards underfoot like verglas and loose rocks. After crossing snow or water, make sure your shoes' soles are dry enough for the slab you're planting your foot on. If a body position or climbing line doesn't feel right, back off and consider another plan of attack. Much of the route above the Upper Saddle is a scramble but even those sections have hazards.

Take the time to be safe.

"Many of our clients are exhausted and at the limits of their abilities, and they make mistakes. What this means is that our clients are trying to kill each other, they're trying to kill themselves, and they're trying to kill you. Each of us needs to remember this at all times. That's our job." Dave Carman, Exum Mountain Guides, as told in the Outside Magazine story “The House of Rock".

If you're on a guided climb, every climber has a

responsibility to look after their own safety and the safety of

others not only because guides sometimes make incorrect assumptions

about everyone's safety but because that's your job.

1939 was an interesting time to be climbing. 19-year-old Margaret Smith Craighead was on the

first manless ascent of the Grand Teton

in 1939. It took them 4 hours and 30 minutes to reach the summit from

the Lower Saddle. By the age of 16 she had climbed most of the major

peaks in the Teton Range. Within a week of her manless ascent,

13-year-old

Bill Johnston

from Casper could be seen

climbing the Grand Teton. And a 17-year-old Jim Crooks, who was an occasional climbing

partner of 16-year-old

Fred Beckey,

was guiding a group of 19 people up the

Owen-Spalding route. Beckey also started climbing in the Tetons in 1939. Fred's Summit Register.

40-year-old Joe Hawkes made his 5 hour and 21 minute FKT round-trip in 1939. That was also the year that Lloyd and Mary Anderson, who founded REI in 1938, descended on the Tetons with a group of over 100 members of The Mountaineers. Their trip was documented in the above-mentioned 1939 Annual of The Mountaineer.

40-year-old Joe Hawkes made his 5 hour and 21 minute FKT round-trip in 1939. That was also the year that Lloyd and Mary Anderson, who founded REI in 1938, descended on the Tetons with a group of over 100 members of The Mountaineers. Their trip was documented in the above-mentioned 1939 Annual of The Mountaineer.

Kids were climbing the Grand back in the early 30s, too. A 13-year-old Jay P. Bartlett and his 11-year-old brother Frank of Ogden, UT reached the summit on July 15th, 1933 with Paul Petzoldt

as the guide, and in a single day from the valley floor. One year

later, 10-year-old Fred Eriksson of Stockholm, Sweden, bagged the summit

on August 27th, 1934. The Salt Lake Telegram

covered that ascent. At least three 13-year-olds and three 11-year-olds

cruised to the summit in the early 30s according to the 1937 version of GTNP's Autumn Nature Notes published on npshistory.com.

You can peruse the old

GTNP Summit Registers

on

Paul Horton's great website if you want a glimpse into the

climbing history of the Tetons.

Let's get back to our climb

The Upper Saddle is approximately 600 feet below the summit.

The Owen-Spalding Route

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

AVOID STANDING DIRECTLY BELOW THE RAPPEL AREA

THAT IS A ROCKFALL ZONE

THAT IS A ROCKFALL ZONE

The exposed Belly Roll is at the very NE corner of the Upper Saddle

This area can be windy, freezing, and backed up with climbers. Waiting makes the cold worse. Morning temperatures in the 30s are not uncommon around the Upper Saddle

during the summer. Sometimes 20s with a cold front. That's before wind chill is calculated. People have bailed because they didn't have gloves during the peak

summer season and the climbing rangers have rescued climbers who lost dexterity and grip strength due to low temperatures. While it's not always freezing or clogged with climbers, you should be prepared for that possibility.

Most free-soloing climbers can safely pass other climbers by the exposure. It's good etiquette to make sure those climbers are comfortable with the idea, and that those climbers don't put your safety at risk, or vice versa.

Variation that's not for beginner climbers:

In the above photo, the Wittich Crack (video & first ascent) is rated a 5.6 (CGTTTR) to 5.7 (MP). It's not uncommon to run into slick conditions near the top of the Wittich after a cold, wet spell because it's well shaded. However, it's not part of a major drainage area like the 1st Entrance of the Double Chimney. It's a variation for stronger climbers who don't want to wait behind OS climbers. The crux is the exit from the top (climb left).

In the above photo, the Wittich Crack (video & first ascent) is rated a 5.6 (CGTTTR) to 5.7 (MP). It's not uncommon to run into slick conditions near the top of the Wittich after a cold, wet spell because it's well shaded. However, it's not part of a major drainage area like the 1st Entrance of the Double Chimney. It's a variation for stronger climbers who don't want to wait behind OS climbers. The crux is the exit from the top (climb left).

Let's get back to our standard route options....

OS's Exposure

The above video takes a look at the Owen-Spalding's exposure between the Belly Roll and the 2nd Entrance of the Double Chimney. It's redundant with multiple members of a local coed soccer team making similar moves; however, it gives you a good feel for what to expect. Many of the soccer players had no prior climbing experience.

Belly Roll - going over the detached rock

Willow riding the bottom of the Belly Rol

Belly Roll - climbers using the lower ledge

Video of two climbers going under the Belly Roll

Video of two climbers going under the Belly Roll

We're not aware of any accidents ever happening while passing the Belly Roll.

The ledge directly below the Belly Roll is tiny at its southern end. In the video above, the first climber jumps off the southern end. Had he landed on a small patch of ice, or lost his balance, he could have sailed over the cliff. You can gently step off the end if you're tall. Obviously, taller climbers have greater flexibility in their choices since their reach is longer. The shorter climber climbs over the lip of the cleavage once he passes the Belly Roll.

The ledge directly below the Belly Roll is tiny at its southern end. In the video above, the first climber jumps off the southern end. Had he landed on a small patch of ice, or lost his balance, he could have sailed over the cliff. You can gently step off the end if you're tall. Obviously, taller climbers have greater flexibility in their choices since their reach is longer. The shorter climber climbs over the lip of the cleavage once he passes the Belly Roll.

The ledge between the Belly Roll and the Crawl. Upper Saddle in background

Looking toward the Crawl from the ledge.

The Crawl with access to the Double Chimney in background - descent

Go outside, inside, or partly outside & inside the Crawl.

Glenn Exum with partner in the Crawl

Glenn is below the First Entrance of the Double Chimney and he has one foot on the ledge variation used to access the 2nd Entrance of the DC.

The Crawl - descent

Crawl - descent

The area right behind the climbers and in front of the photographer can be sketchy. Loose rocks, snow, water and ice are common at this location. Additionally, the rock face is sloping into Valhalla Canyon. Be careful as you leave the Crawl — see below....

Climber at the Crawl

This picture will give you a feel for what's underneath you if snowy conditions hide features. Unstable snow can slide off the slope and take you with it. Stay close to the wall. FYI: There's an old piton on the wall above you as you come out of the Crawl. A few small handholds are along the wall.

A questionable 'cornice' over the exposure

You have a couple of options to choose from to gain the interior of the Double Chimney. The 1st Entrance is the crux. The 2nd Entrance is considered to be the fastest and easiest variation. And it's the most common variation taken by soloing climbers. The two entrances are about 12 to 15 feet apart.

Let's look at the variations in more detail starting with the 1st Entrance..

1st Entrance of the Double Chimney

Too many climbers were backed up at the 1st Entrance in the above image. And more were behind them. Using the 2nd Entrance would have been a better choice to speed things along. On the Owen-Spalding route it's important to keep things moving if others are behind you. This is a trade route. If a more efficient variation presents itself, please consider taking it. Novice climbers will have a much easier time utilizing the 2nd Entrance when it's dry and it's the recommended option.

There's a variation directly above the horn at the 1st Entrance (directly above Ellingwood's right arm). It runs up a tiny chimney/drainage. It can be used to access a ledge that runs along the top of the Double Chimney's Open-V variation (discussed further below). It's a good way to bypass slow climbers if this variation is dry. It can also be used as a shortcut to the Catwalk. It's fairly easy; however, it's usually avoided because it's a drainage for water flowing off the Catwalk. It can be dangerously wet, icy and slimy. Downclimbing that variation has exposure with holds that look questionable above a drop to your death. Non-climbers may find it intimidating even when dry.

Drainage variation

The above guide is grabbing a horn and muscling her way over it with some stemming behind her. There's a small depression near her rear foot to use for leverage. Notice she is only wearing approach shoes. Or trail running shoes with a solid grip.

This is one spot where sticky rubber can make a big difference on how you judge the difficulty of the route. Many climbers give this entrance a rating higher than 5.4, including us. The 2023 edition of A Climber's Guide to the Teton Range gives the Double Chimney a 5.5 rating; however, it doesn't even highlight the 1st Entrance on its marked up route image. And it keeps the overall route rating at 5.4. Go figure. Some feel the entire route only has a 5.4 rating because of the 1st Entrance. Either way, it's still a cruxy, exposed maneuver for many OS climbers. If you're more runner than climber, you might find the 1st Entrance quite challenging.

The 1st Entrance is often wet or icy. During the winter, snow can build up here and provide a nice step below the horn which makes this an easy option.

This is one spot where sticky rubber can make a big difference on how you judge the difficulty of the route. Many climbers give this entrance a rating higher than 5.4, including us. The 2023 edition of A Climber's Guide to the Teton Range gives the Double Chimney a 5.5 rating; however, it doesn't even highlight the 1st Entrance on its marked up route image. And it keeps the overall route rating at 5.4. Go figure. Some feel the entire route only has a 5.4 rating because of the 1st Entrance. Either way, it's still a cruxy, exposed maneuver for many OS climbers. If you're more runner than climber, you might find the 1st Entrance quite challenging.

The 1st Entrance is often wet or icy. During the winter, snow can build up here and provide a nice step below the horn which makes this an easy option.

1st Entrance seen from above

Too many climbers were backed up at the 1st Entrance in the above image. And more were behind them. Using the 2nd Entrance would have been a better choice to speed things along. On the Owen-Spalding route it's important to keep things moving if others are behind you. This is a trade route. If a more efficient variation presents itself, please consider taking it. Novice climbers will have a much easier time utilizing the 2nd Entrance when it's dry and it's the recommended option.

FYI: Roped parties with more than 3 people are not appreciated on the trade routes and they're strongly discouraged from assembling. But, there's no rule against it. And some move with speed. The rangers discouraged it on their old blog, and the guidebook does. Free-soloing parties usually don't care. They'll pass when it's safe to do so.

Downclimbing the 1st Entrance isn't common but it's a good option under some circumstances. Goes quicker if you're tall and you can lower yourself off the horn.

Albert Ellingwood is atop of the Austrian mountaineer

Hermann Buhl. They're at the 1st Entrance of Double Chimney. The American mountaineer

Carl Blaurock

took the photo in

1924. Carl was the first person to summit all fourteeners in the

contiguous United States. Ellingwood made his first climb of the route a year earlier with the first woman to summit the Grand Teton, Eleanor Davis. Eleanor and Albert were the 3rd party to officially summit. They were actually on the 4th ascent up the Grand because members of the Owen party climbed twice in 1898. This shoulder stand is called a courte-échelle (short ladder). In the 1960s, this was the recommended climbing move in Bonney's guidebook.

Reinhold Messner wrote this about the legendary Austrian climber Hermann Buhl: “Had Hermann Buhl been born forty years later he would surely have been one of the leading sport climbers, and a classic mountaineer without equal.”

Reinhold Messner wrote this about the legendary Austrian climber Hermann Buhl: “Had Hermann Buhl been born forty years later he would surely have been one of the leading sport climbers, and a classic mountaineer without equal.”

Variation that's not usually taken by novice climbers:

There's a variation directly above the horn at the 1st Entrance (directly above Ellingwood's right arm). It runs up a tiny chimney/drainage. It can be used to access a ledge that runs along the top of the Double Chimney's Open-V variation (discussed further below). It's a good way to bypass slow climbers if this variation is dry. It can also be used as a shortcut to the Catwalk. It's fairly easy; however, it's usually avoided because it's a drainage for water flowing off the Catwalk. It can be dangerously wet, icy and slimy. Downclimbing that variation has exposure with holds that look questionable above a drop to your death. Non-climbers may find it intimidating even when dry.

Let's look at the 2nd Entrance variations.....

Climber heading for the 2nd Entrance

This climber's handholds are along the obvious

cleavage above the sloping rock. Some

footholds are low on the slope, some high.

The crux is the last move off the sloping face as he gains the

interior of the chimney. It demands attention. The footholds are small and some might be more frictiony than you're

expecting.

Gaining the 2nd Entrance

Climbers have fallen to their death around this area. One involved a lightning strike which took the life of Brandon Oldenkamp (21) and sent 15 others to the local hospital. Another involved Don Ivie (44) who was soloing the route. He was alone and his exact location & the cause of his fall is unknown. There have been others.

In the video below, Bob takes a slip as he tries to enter the 2nd Entrance of the Double Chimney. He recovers and goes on to make some GT climbing history.

A big slip that didn't slow him down

Watch for loose rocks as you enter the chimney.

Watch for loose rocks as you enter the chimney.

We will take a moment to say something about departure times from the trailhead. In August of 2017,

Bob Harris, seen above, made the first known ascent up the Grand by an individual with Down syndrome. His team departed the

trailhead around daybreak and arrived at the summit around 5:15

p.m. Had they arrived at the Upper Saddle in the morning it would have

been a much longer day and more dangerous. The climbing was cold and

icy in the morning. Some climbers turned around. The weather was nice

and warm later in the day with much safer conditions. After climbing,

they camped overnight at the Lower Saddle. Not every day will provide

great afternoon weather for a delayed start; however, a late start is a common tactic with a thin layer of overnight icing.

The small ledge below these climbers is shown in the next photo. It's the Lower Ledge variation.

Lower Ledge Variation - heading for the 2nd Entrance

From the 1st Entrance, downclimb to a narrow

ledge that runs toward the 2nd Entrance. Directly below the 2nd Entrance

you'll find

a small step and some small holds on the wall in front of you.

Just a quick aside to say that climbers can be below you anywhere on the Grand. Certainly below the climber shown here. Be mindful about rockfall.

This is a funky spot for belaying. We ascended the 1st Entrance to avoid these climbers. Waiting on four climbers might take more time than it takes to reach the summit. As discussed later, some climbers get to the summit in under 15 minutes from here.

A ledge system between the two climbers continues to the north. It goes to the Great West Chimney and eventually connects to the 2nd Ledge of the North Face. Many climbers on the North Ridge will traverse to the Owen-Spalding to finish their climb. There's also a Double Chimney Bypass that they can utilize which goes directly to the Owen Chimney. The DC Bypass is sometimes useful if you wish to avoid a busy Double Chimney. For example, we have used it when the 1st Entrance was too wet and the 2nd Entrance was clogged with people. The DC Bypass is off-route and we won't rate it but it's pretty easy to ascend if you have sticky shoes and dry rock. It's shown below:

Double Chimney Bypass (green line)

If the first step in the wall at the start of the bypass looks too difficult just go a little further to the north and you'll be at a series of smaller steps. You might find a nice snow-step early in the season. This area can get icy and slimy during the summer.

Renny

The 2nd Entrance

Jane looking up from the 2nd Entrance

The climber looking at the photographer is at the location where the 1st Entrance tops out. The next photo shows what he sees as he looks down at the 2nd Entrance....

We will look at several variations to move around the Double Chimney:

Stemming to move in or out of the Open-V is common. On a descent, some climbers are facing the opposite direction but still throwing a leg in the same spot to the north. It's kinda awkward, and challenging if it's icy.

The rarely used crack along the southwest corner of the Open-V ends on a nice ledge. Just walk off to the east above the Open-V.

Stemming to move in or out of the Open-V is common. On a descent, some climbers are facing the opposite direction but still throwing a leg in the same spot to the north. It's kinda awkward, and challenging if it's icy.

The Open-V. Tunnel variation below.

Photographer is on a ledge above the Open-V.

Jane Maus on her 2025 Grand Teton FKT run using the Northern Slot

They went up the Upper Exum, down OS

The tunnel variation is considered easier. It's sometimes clogged with ice or icy snow. Take your time and consider the best variation for you.

The climber on the flake's edge is heading for the northern slot (left side).

Climber in the northern slot

Two free-soloing climbers, one descending

The climber on the flake's edge is heading for the northern slot (left side).

Photographer is on a ledge above the Open-V.

She wiggled her way down the opening at the very bottom of the slot. She went up the Open-V, stepping into it like it was a stair. That was much faster for her. “I’m not a traditional rock climber. More like, scrambling that pairs nicely with running. That’s really my bread and butter,” she said.

Exiting the Open-V to the southeast (right)

Many climbers exit in the opposite direction. Choose any.

On July 4, Jackson Hole Mountain Guide Allan Bard (44), who was also a guide of the Palisades School of Mountaineering in Bishop, California, died after slipping on ice and falling 130 feet on a rope while leading the Double Chimney.

When icy, ice is almost always where you don't want it in the Double Chimney.

Taking a break at the entrance to the Open-V

North Slot directly below photographer

Rope in Tunnel. Open-V at top of image. The detached flake used to be upright, creating two chimneys.

Let's go back and look at the tunnel variation.

Downclimbing the tunnel variation.

The scramble between the Catwalk & Main Rap area

Climbers sometimes crab craw down the rock during the descent to reach the flattest part of the Catwalk variation. You probably won't recover (YOU WILL DIE) if you lose your balance, slip or trip in this area. So, at the very least stay low and go slow if you're new to this. Gravity and momentum are two hazards working against you as you downclimb this area. FKT runners move very quickly but their hands are brushing the rock along the way.

The "stay low, go slow" scramble between the Catwalk and the Rap Overlook

You're likely to see many more people above the

Owen Chimney & Catwalk. No matter their route to the summit, almost

everybody uses the same descent path off the summit which is the upper

half of the Owen-Spalding route.

Another look up

You'll pass an old piton or two through the crux. If it's really icy, overlooked holds along the northern wall may prove useful. Depending upon your location in the Owen Chimney, it's sometimes possible to climb out of the chimney and access the bypass to your south, or vice versa.

If you wish to climb with crampons but don't have any, they can be rented from Teton Mountaineering in Jackson. Make sure they fit, and fit securely. Large boots may need a longer extension bar.

Exact same location as above

The free-soloing climber is exiting the lower part of the tunnel (she went up the Exum Ridge). The DC's tunnel variation is a tight fit with a backpack. You're on your hands and knees once inside. When dry, it's a very popular variation. Fairly quick and easy. Well, we say that but it's not easy and quick for everyone.

This is where you pop out of the tunnel on the ascent.

Some struggle, some cruise along

The common exit from the DC

The slabs by the climber have modest handholds when dry but they work fine. Those holds can become plugged with ice. Consider a slightly more northern exit when icy.

The rope is coming out of the tunnel variation. The belayer is at the bottom of the Owen Chimney. The Owen Chimney runs slightly sideways

to the southeast so you won't be able to fully see its interior as you exit the

Double Chimney.

Again, we think the holds to the left of the young woman are better than those along the direct line by the rope, especially under icy conditions. A tiny collection of pebbles sometimes litters the slabs. They're also a slip hazard.

Just to her right begins a shortcut to the Catwalk for climbers using that variation (see below).

Again, we think the holds to the left of the young woman are better than those along the direct line by the rope, especially under icy conditions. A tiny collection of pebbles sometimes litters the slabs. They're also a slip hazard.

Just to her right begins a shortcut to the Catwalk for climbers using that variation (see below).

Overview Owen Chimney & Catwalk

Variations

We're going to start by looking at the Owen Chimney's Southern Bypass that forks off of the Owen Chimney. We'll look at the Catwalk and the Owen Chimney in more detail in just a second.

The Southern Bypass variation is not usually taken:

The climber's rope is coming out of the Owen Chimney. He took the first "opening" in the chimney to reach the start of the Owen Chimney's Southern Bypass.

We're going to start by looking at the Owen Chimney's Southern Bypass that forks off of the Owen Chimney. We'll look at the Catwalk and the Owen Chimney in more detail in just a second.

The Southern Bypass variation is not usually taken:

This bypass has been used for decades and mentioned in older guidebooks. You probably won't see anyone using it. The very bottom of this variation doesn't get much sunshine and it's often icy when the Owen Chimney is icy. A novice climber will probably find the bypass more

difficult than the Owen Chimney when both are dry.

You can also access the sunnier part of the bypass from the Catwalk if you travel a short

distance up the Catwalk and look for the easiest location to gain a

small ledge above you. That ledge runs above the entire length of the Catwalk's flat section. The climber above is standing on it.

Sunnier (usually) part of the Southern Bypass

The Catwalk Variation

We'll look at the Catwalk variation before looking at the Owen Chimney variation.

Two ways to the Catwalk

The climbing line that runs directly to the Catwalk from the Double Chimney goes by a detached rock that looks suspicious (see break in line) It's been a reliable climbing rock for decades but

there are options on both sides in case you wish to avoid it. Easy climbing. This is

the fastest line to the Catwalk.

The

climber in the blue jacket is taking the direct line to the

Catwalk from the Double Chimney. The climber in the red jacket is at the

base of the Owen Chimney.

Looking back from inside the Owen Chimney

This is the view from just above the first opening in the Owen Chimney. See the word "Access" in yellow type? In the next image, the climber is by that spot.

Downclimbing to the Catwalk (unseen)The photographer is at the Owen-Chimney Bypass. The access to the Catwalk is behind the climber and around the corner (see below). There's an old piton in the wall where he turns the corner.

Another look

The Catwalk - looking southish. Climbers are descending.

The Catwalk is the preferred descent route for most free-soloing climbers and for almost all free-soloing FKT runners. FKT runners who are strong climbers should consider the Owen Chimney during an ascent if it's dry and empty. It might be their fastest option. Kilian Jornet used it while training for his FKT.

Ice is common near the location where the last climber is. It's a significant drainage area. The climbers went past a sheet of ice covering about five feet of the Catwalk and the wall. If you do find ice, it might be easy to step over top of it while using a hold on the wall. Sometimes you can scramble away from the wall to the west and find enough dry patches to pass a difficult section of ice. Not everyone is comfortable moving away from the wall but this is often an excellent option. You can always chip away at the ice if it strikes your fancy. Try a loose rock. A couple old pitons run along the Catwalk's eastern wall.

At times, verglas can be hard to quickly recognize if it's a tiny patch. It's common on the Owen-Spalding.

At times, verglas can be hard to quickly recognize if it's a tiny patch. It's common on the Owen-Spalding.

Climbers sometimes crab craw down the rock during the descent to reach the flattest part of the Catwalk variation. You probably won't recover (YOU WILL DIE) if you lose your balance, slip or trip in this area. So, at the very least stay low and go slow if you're new to this. Gravity and momentum are two hazards working against you as you downclimb this area. FKT runners move very quickly but their hands are brushing the rock along the way.

Looking up at Sargent's southern approach

If

you take the Catwalk, you'll end up by the photographer's location

in the above picture. These climbers

are heading for

the rappel back to the Upper Saddle.

The Owen Chimney variation

Let's go back and look at the Owen Chimney variation for those who don't want to take the Catwalk.

The Owen Chimney is part of the original route. It can get backed up pretty quickly with a group of climbers. We strongly recommend the Catwalk if things are going slowly.

The 75 foot Owen Chimney was referred to as the Spalding Chimney in Bonney's guidebook from the 1960's. And the entire route was sometimes called the Spalding-Owen Route. Both were more fitting names in our opinion as Spalding led the first ascent, was more modest about the achievement and was the better climber. Owen seemed a little too infatuated with a grandiose sense of self-importance when it came to his climbing.

The

Owen Chimney is not very difficult when dry. It's a mix of steppy &

sloping rock. Many of the flat steppy footholds are small and thus much more

challenging under icy conditions. And there aren't too many monkey-bar handholds where you would want them when it's icy.

As always, soloing under icy conditions is not recommended but stuff happens, or perhaps you have the experience to handle it. The soloing climber's rule of thumb is to not go up what you can't get down. Getting up an slick & icy chimney is usually easier than going down one.

As always, soloing under icy conditions is not recommended but stuff happens, or perhaps you have the experience to handle it. The soloing climber's rule of thumb is to not go up what you can't get down. Getting up an slick & icy chimney is usually easier than going down one.

The bottom of the chimney sometimes collects icy snow that sticks around well into summer, or accumulates again after cold, wet weather. Additionally, it's not always easy to tell if ice is covering critical footholds in the chimney as you look at it from below. You might be surprised by heavy icing as you near the upper section.

Sublimation is the most

common way for snow and ice to disappear when temps remain below

freezing. It's one reason why nice conditions in October can never be ruled out.

On July 20, 2023, Braydan DuRee of Kuna, Idaho died after falling 40 to 50 feet from the Owen Chimney. DuRee was wearing a helmet, using a rope and leading the route when he fell. No word on what caused the fall but conditions weren't totally dry, and the route was icy before the climb. When he fell, his protection popped out of its placement. The Accident Report was included in a story on the JHN&G website.

Placing multiple cams in an icy Owen Chimney (mid-July)You'll pass an old piton or two through the crux. If it's really icy, overlooked holds along the northern wall may prove useful. Depending upon your location in the Owen Chimney, it's sometimes possible to climb out of the chimney and access the bypass to your south, or vice versa.

If you wish to climb with crampons but don't have any, they can be rented from Teton Mountaineering in Jackson. Make sure they fit, and fit securely. Large boots may need a longer extension bar.

Exact same location as above

More thin snow than ice. Maybe tacky snow. These are manageable conditions for an experienced alpine climber who's soloing without crampons but the slick conditions often require greater care, skills and creativity in this chimney.

Owen Chimney

We're looking north in the photo. This ledge system runs between the Great West Chimney and the Exum Ridge.

You might find some privacy by the Great West Chimney if you need to take a piss. There isn't much privacy on this route but there are a few nooks and crannies. You can also head in the opposite direction, see below. You may run into some climbers if you head south because the ledge system runs by the top of the Pownall-Gilkey route which is regularly guided by JHMG.

We're looking north in the photo. This ledge system runs between the Great West Chimney and the Exum Ridge.

You might find some privacy by the Great West Chimney if you need to take a piss. There isn't much privacy on this route but there are a few nooks and crannies. You can also head in the opposite direction, see below. You may run into some climbers if you head south because the ledge system runs by the top of the Pownall-Gilkey route which is regularly guided by JHMG.

Overview of Sargent's Chimney

Sargent's

Chimney fans out at its base. The southern wall at the base of

Sargent's points toward the Main Rap. The northern wall points toward

the top of the Owen Chimney. Climbing the southern side of Sargent's is the

quickest line to and from the Catwalk. The northern access from the top

of the Owen Chimney might be the easiest for children but we can't

really say with certainty that one line is better for any age or skill

group. There are many ways to fully enter and exit this chimney.

Sargent's Chimney is named after Jessie Sargent.

Her husband, Frank Sargent, was of the Governor of Massachusetts from

1969 to 1975. On Aug 9, 1960, she broke her ankle in an accident while on a guided climb in the chimney. Sargent's was often called the

Fissure Chimney before then.

On August 4th, 1988, a Centerville, Utah, man was leading his two sons up the Owen-Spalding Route when he slipped on verglas near the 13,400' level and fell about 45' onto a ledge, fracturing his radius, pelvis and ribs and sustaining a hemopneumothorax. The call for help might have been the first time a cell phone was used to report a climbing accident in GTNP (using another party's phone: commercial guides). If true, that was during the dark ages of analog cell phones with fewer towers. Others have said the first emergency call from a cell phone was on Aug. 18, 1994, after a rappel anchor failed and a person fell 200 feet while on the Exum Ridge.

On August 4th, 1988, a Centerville, Utah, man was leading his two sons up the Owen-Spalding Route when he slipped on verglas near the 13,400' level and fell about 45' onto a ledge, fracturing his radius, pelvis and ribs and sustaining a hemopneumothorax. The call for help might have been the first time a cell phone was used to report a climbing accident in GTNP (using another party's phone: commercial guides). If true, that was during the dark ages of analog cell phones with fewer towers. Others have said the first emergency call from a cell phone was on Aug. 18, 1994, after a rappel anchor failed and a person fell 200 feet while on the Exum Ridge.

The snow often makes the scrambling easier and faster. In the middle of the image, there's a triangle-shaped tip of a rock sticking out of the snow with a black rectangular inlay. Can you find the inlay in the next photo?...

The Hidden Exit